Factors leading to The New Zealand Wars

The Land

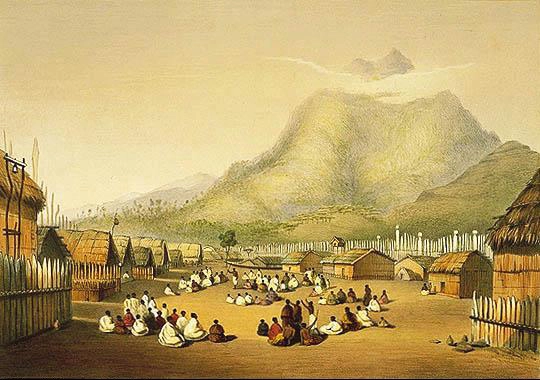

Before the arrival of European settlers, Māori possessed distinct patterns of land ownership with 'rules' and principles guiding iwi (the tribes) as to how land was to be treated, valued and, above all else, protected.

A marae at Kaitotehe, near Taupiri mountain, Waikato district.

- The arrival of Europeans changed all this, primarily because Māori and Pākehā (white settlers) perceived the importance of the land very differently:

- For Māori, the land was owned communally. Land could be gifted but not be traded permanently for goods or money. Land is the source of tribal history, identity and mana (influence). The land bore the names of ancestors, and the stories of ancient times were personified in landforms.

- For Pākehā, used to English law, land was owned individually, or by a 'legal entity' eg. a family. Land could also be freely exchanged, it therefore possessed value as a commodity for sale and purchase. Land was improved, cultivated, and used as a physical asset; land 'lying idle' was seen as wasteful. Land was the source of social and political position as well as a source of wealth. Owning land as an individual also allowed them the vote, as long as they were male, over 21 years old.

Contest for Land Page further readingEuropean Settlers

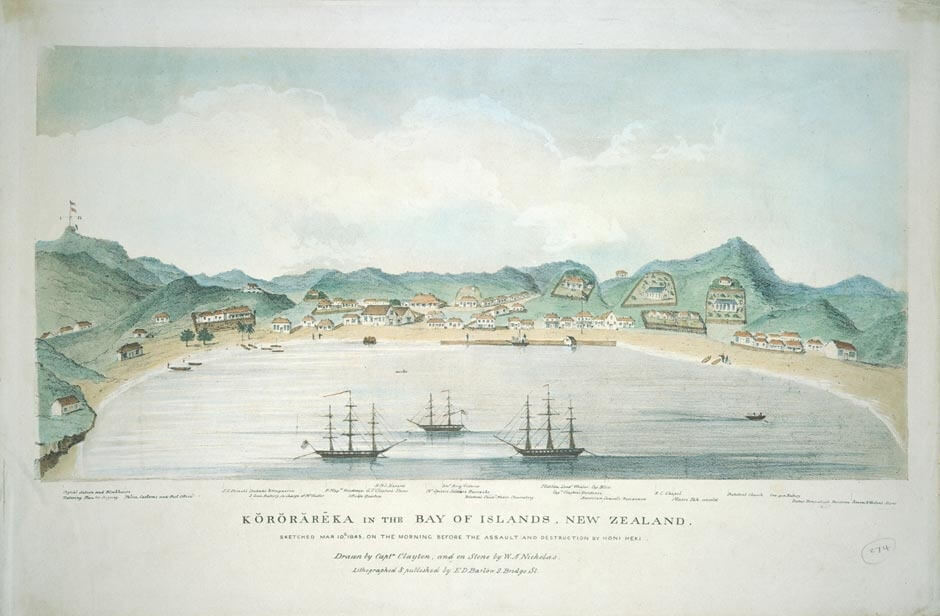

The First European settlers came from Australia and Britain in the 1790s. The first 'British community' was a sealing camp in Doubtful Sound established in 1792 (it survived for two years).

A painting of Kororareka the morning before Hone Heke attacked.

- The early European settlers were primarily interested in the coastline, hunting for whales and seals. Slowly Europeans moved inland for timber, flax and food, however, access proved difficult, and so these early Pākehā settlers generally established peaceful relations with local Māori communities. With many of them marrying into Māori tribes and became 'Pakeha Maori', living amongst Maori and accepting Maori lore and conventions.

- Migration ramped up after 1840 when Edward Gibbon Wakefield, and his New Zealand Company, established The Wakefield Settlements, these were modeled on a vision of pre-industrial Britain that had probably never existed. However, it was a concept powerful enough to bring many thousands of British migrants across the world to New Zealand. These new Wakefield settlements were ambitious in their planning, but the entire Wakefield scheme proved impractical, little or no provision was made for Māori.

- Increasingly, land disputes began to dominate relations between Wakefield and Māori. This was fuelled in part by a deep-seated antagonism between the New Zealand Company and the newly-established Governor, Captain William Hobson. Both groups were struggling for control of New Zealand, and either through design or ignorance, Māori were not seen as a factor in this dispute, a point that was not lost on them.

Impact of New Settlers further readingThe Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi was signed on 6 February 1840, by Captain William Hobson (The first Governor, and Crown representative) and approximately 40 chiefs. Eventually, about 500 chiefs signed one of the half dozen copies that circulated the country. For Māori, the Treaty of Waitangi incorporated several undertakings that the Crown did not fulfil. For example, Maori people were not included when the 'Executive Council to govern New Zealand' was established by Governor Hobson. Māori experienced a gradual but definite imposition of British law and institutions at the expense of traditional Māori law and institutions.

- Some significant chiefs chose not to sign, especially Te Whero Whero of Waikato, who would later become the first Māori King in 1858.

Impact of The Treaty of Waitangi further reading

A painting of Signing the Treaty of Waitangi.